What do we know about Native Americans in Adams County?

By Karen Hendricks

Adams County is celebrating an interesting birthday this year—its 222nd! Founded on January 22, 1800, Adams County was carved out of—and originally part of—York County.

But the land, of course, existed before then. What do we know about life in Adams County prior to 1800? We went in search of Native American ties—and found a treasure trove of history.

First, Foreign Concepts

“When Europeans came over, they saw large swaths of forest and thought of Adams County and this land as unoccupied—there’s a European term from Latin called ‘terra nullius’ which means ‘empty land’—and therefore theirs for the taking,” explains Benjamin P. Luley, Ph.D., an anthropology professor at Gettysburg College.

But was Adams County truly empty or unoccupied?

“We know there was no contact between the first European settlers and Native Americans,” says Andrew Dalton, executive director of the Adams County Historical Society.

There were, however, Native Americans nearby in central Pennsylvania.

“They had centralized around larger river systems like the Susquehanna,” Dalton explains.

But prior to that, Adams County was actually home for many Native American peoples—and we know this, Dalton says, because they left thousands of clues behind in the form of stone artifacts.

“The Susquehannock tribe was in the area—they were the closest group of Native Americans. It’s possible these people were ancestors of the Susquehannock, but we really don’t know,” Dalton says.

But one thing we do know: Native Americans didn’t have the same concept of land ownership as Europeans.

“It’s important to dispel this idea that this was empty land, because we know Native Americans’ interactions with the landscape were deep interactions—a symbiotic relationship with the landscape—and even if they weren’t physically living there, it was still very much part of their world,” Dr. Luley explains.

(now Philadelphia). In the early 1680s, a Treaty of Friendship was made between the chiefs of the Lenape and William Penn. Eventually, the Lenape would lose all claims to the land they had inhabited for centuries and were forced West.

Preserving the Past

And that land—Adams County’s earth—held many clues. Over the years, Dalton says, numerous Adams County residents discovered and contributed Native American artifacts to the historical society, a collection that today has grown into the thousands.

Many of those artifacts will be on public display for the first time ever, when the historical society’s new museum, Gettysburg Beyond the Battle, opens in spring 2023.

Organized chronologically, the museum begins with Adams County’s prehistoric history—think geology and dinosaurs, even a meteorite. Native American history comes next, then tracing and linking Adams County’s history to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Civil War periods.

“How the people dealt with the battle and its aftermath—that’s the largest section of the museum,” Dalton explains. “There’s an immersive room that allows visitors to step inside the living room of a family caught in the battle, and there’s lighting and special effects—you’ll feel like you’re there in that moment.”

Dalton credits a great team of experts with bringing the museum—and its history—to life, including a renowned Washington, D.C. museum designer who also contributed to the acclaimed Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia.

Evidence in the Earth

Adams County’s waterways are the best conduits for its Native American stories. That’s because most of the artifacts were unearthed along Adams County’s creeks and streams, where Native Americans would have lived.

“These are 2,000- to 4,000-year-old artifacts, which puts into perspective how long this time period was before our ancestors arrived,” Dalton says.

The historical society, working in consultation with

Dr. Luley, sifted through these treasures—comprised of stone and pottery—and made tough choices about which pieces to put on display in the museum.

“We tried to pick a variety of items to illustrate the different ways that Native Americans lived, hunted, and cooked. And we also picked artifacts that were found along a variety of waterways—Marsh Creek, Rock Creek, Conewago Creek, and Middle Creek near Fairfield—to represent the geography of Adams County,” Dalton explains.

The finely-chiseled artifacts are all being classified and labeled according to their specific functions: projectile points, bannerstones, broadspears, arrowheads, grinding stones, and more.

“We have a lot of knowledge related to the stone tools we find, about how Native Americans were hunting and gathering, having interactions with the environment—it’s a window that archaeologists have,” Dr. Luley explains.

One of the most interesting and unusual artifacts is a large rock called a quern stone. About 3 feet long, it has a hollowed-out area that would have been used by Native Americans for grinding and mixing ingredients. Discovered on a Berwick Township farm, the stone is believed to have been crafted by Native Americans more than 3,000 years ago. Museum visitors will even be able to run their fingers over this treasure—literally touching history.

Dalton hopes it sparks a greater appreciation for Adams County’s past.

“These artifacts are tools to tell these powerful stories people may not have heard before,” he says.

Indeed, the museum’s development comes at a time many consider to be a reckoning.

“I think people are looking at all of history, and they’re looking for a more honest story. I think they want to hear the truth—some is good, some is bad, some is inspiring, and some is painful, but I think it’s important that we look at all of it and learn from the past,” Dalton says. “We’re trying to make sure that every part of Adams County history is represented without pushing any kind of agenda—we want an objective view.”

Gettysburg’s place in history, as the turning point of the Civil War, the place where the fate of our nation was saved, occurred during three days in 1863. Now, a larger historical context can be explored, stretching back more than 3,000 years in and around these hallowed battlefields.

“We think so much about the European presence in Pennsylvania, and obviously with Gettysburg, you talk about the battlefield—and it’s such a small fragment of the history of this area,” Dr. Luley says. “So that’s actually one of the things I really like about this collection—it give you a deeper time and depth to the humans who’ve been living here.”

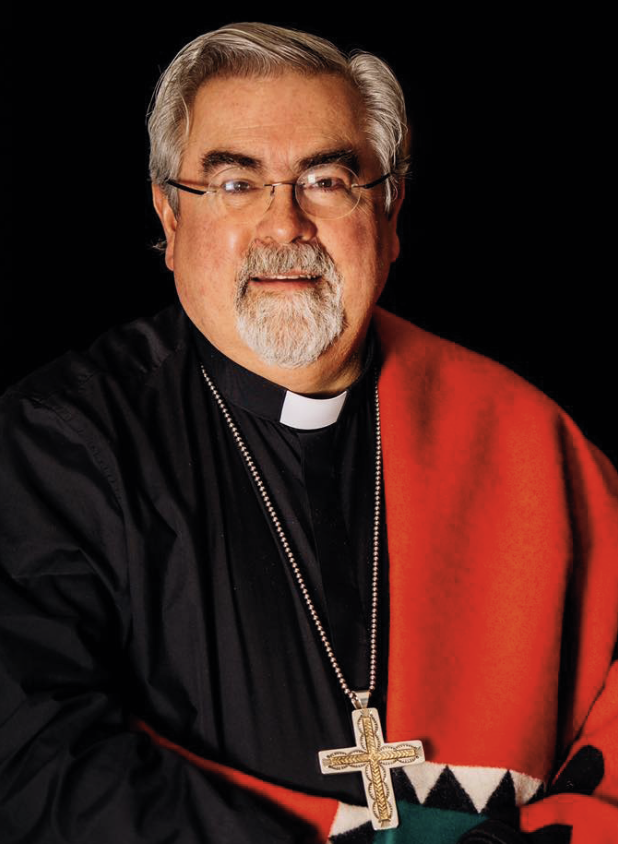

From Osage Child to Child of God:

Meet Guy Erwin, Ph.D.

One of today’s most prominent Native Americans in Adams County is Guy Erwin, Ph.D., president of United Lutheran Seminary’s Gettysburg and Philadelphia campuses. How did a child, born and raised in Oklahoma’s Osage Nation (reservation) to a non-Christian family, not only come into Christian faith, but become the first Native American bishop and first openly gay partnered bishop, nationwide, in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America?

That path, like many paths in life, has taken Dr. Erwin to many places—yet his sense of ‘place’ is likely very different from yours and mine.

“I’m very acutely aware of where I am all the time,” says Dr. Erwin, 64, who moved to Pennsylvania two years ago from California and Connecticut. He discovered, and was baptized into, the Lutheran faith during his college years at Harvard. Still, Erwin’s childhood home centers him.

“When I lived on the reservation, I knew this was where I was from, in some deep more-than-geographical, almost spiritual, sense,” he explains. “And it’s given me a sense of never quite being where I belong when I’m not there. I feel like I carry with me where I come from. Even here in Pennsylvania, I have Native relatives whose land was lost and who aren’t here anymore … for the most part, they were removed, and I’m always aware of that. I never forget whose land I’m on—it’s the land of the people who were here before the Europeans.”

How does his Native American heritage—combined with German and Pennsylvania Dutch roots—inform his position at the seminary?

“The way I like to think about it is that the church is about the process of bringing the good news of Jesus Christ to people who need to hear it,” says Dr. Erwin, noting that “many people need to hear it in a new way.”

And he may be just the right messenger for today.

“I feel like I’m both a complete insider as a Lutheran seminary president who used to be a bishop—you can’t get more into Lutheranism than that. But at the same time, I stand outside looking in because I wasn’t born into that. So I feel like, in this complicated in-between-ness of belonging and not belonging, I understand what it means to be a church that really needs to reach out to people in the world today.”

And in this historic place—Gettysburg—his own sense of place gives him a unique perspective for us to consider.

“I think our seminary, in our historic locations in Gettysburg and Philadelphia, is uniquely placed to teach our future leaders of the church about what it means to be American Christians. Not in a Christian Nationalism sense, of us being better than everyone else and destined by God to rule. But what it means to be in a place that was founded in part through genocide and financed in part by slavery—and we all live with that. Everyone who lives in the United States benefits from great historic wrongs, I no less than anybody else, and we all have to come to terms with that in our ways,” says Dr. Erwin.

In some ways, being a Christian has its similarities to the Native American experience.

“Christians in part, who are citizens of another place, of a heavenly realm, should be able to detach themselves from shallow forms of belonging and think deeply about what it means to be children of God and brothers and sisters to each other and inhibitors of a land that doesn’t belong to us, that we borrow to live on for a time,” Dr. Erwin says. “And all of that fits in well with what the seminary is all about.”

Setting the Scene

Thousands of years before the town of Gettysburg became “the most famous small town in America,” it was inhabited by Native Americans. It’s just one portion of relatively little-known history that will be showcased in the Adams County Historical Society’s new museum, Gettysburg Beyond the Battle. Executive Director Andrew Dalton shared the scene-setting text for the Native American exhibit panels:

“For thousands of years, indigenous communities settled alongside the region’s creeks and streams. Waterways running through the northern and eastern portions of Adams County flow into the Susquehanna River. In the south and west, they make their way to the Potomac River.”

Links to the Land

Gettysburg College recently developed and issued a statement called a land acknowledgement:

“Gettysburg College is on unceded Indigenous land including the traditional homelands of the Susquehannock/Conestoga, Seneca and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy,

Leni Lenape, and Shawnee Nations, and the connections of Indigenous Peoples to this land continue today. We have a responsibility to honor these connections and we strive to understand our place within the past, present, and future of this Indigenous land by reflecting on our relationships with the human and other-than-human relatives with whom it is shared.”