Civil War Journal

By Sue Boardman & Elle Lamboy

There’s one question almost every American asks themselves (or their spouse, dog, cat, child, phone, etc.) each morning. It’s also almost always the first ice breaker to any conversation: “What’s the weather?”

Thanks to a diligent professor/amateur meteorologist living in downtown Gettysburg in 1863, there are detailed weather reports of each day of the Battle of Gettysburg—July 1-3, 1863.

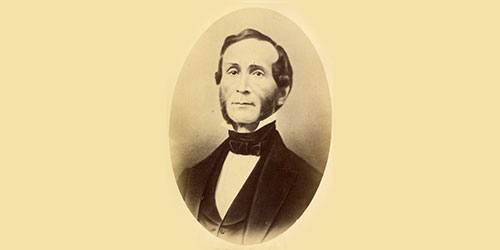

According to “The Pennsylvania College Book, 1832-1882,” Rev. Dr. Michael Jacobs was born in Franklin County, Pa., on Jan. 18, 1808. He was a lifelong learner and very intelligent, graduating “with the second honor of his class and the valedictory.”

His brother, David Jacobs, brought Dr. Jacobs to Gettysburg. David founded the Gettysburg Gymnasium (later to become Pennsylvania College and then Gettysburg College) and was nearing burn-out from being the only teacher at the institution. After fulfilling a teaching obligation elsewhere, Dr. Jacobs was elected professor of mathematics and the natural sciences in 1832. He also privately studied theology.

In addition to being a reverend and respected professor, Dr. Jacobs was also an author. He wrote one of the first published books about the Battle of Gettysburg titled, “Notes on the Rebel Invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania and the Battle of Gettysburg July 1st, 2nd and 3rd, 1863.”

Despite the battle raging through the town and soldiers retreating literally past his front door, Dr. Jacobs knew it would be important to document this experience—even down to the weather. Most of his observations, including a detailed map, are included in his book. But, the weather reports, which he daily logged throughout his 40-year teaching career, were kept in a separate journal and provide excellent detail and insight into the weather during July 1863. He recorded the temperatures and conditions three times a day during the battle: 7 a.m., 2 p.m., and 9 p.m.

Thanks to Dr. Jacobs’ notes, individuals studying the Battle of Gettysburg today know that on July 1, at 2 p.m. it was 76 degrees with a cloudy sky and “a very gently warm southern breeze.” The same time on July 2, the temperature rose to 81 degrees, and at 2p.m. on July 3, it was 87 degrees with “the thunderclouds of summer,” though “tame, after the artillery firing of the afternoon.”

Believe it or not, this detailed weather report played a critical role in today’s visitor experience! Dr. Jacobs’ weather documentation was critical in the conservation of the “Gettysburg Cyclorama” painting located at Gettysburg National Military Park Museum & Visitor Center.

Today, the “Gettysburg Cyclorama” is displayed the way French artist Paul Philippoteaux intended in the late 1880s with an overhead canopy and a diorama with stone walls, broken fences, shattered trees, and a cannon. However, in the late 1990s, it was in danger of ruin due to years of deterioration. In the early 2000s, Gettysburg Foundation, in partnership with the National Park Service, worked with art conservationists to save the painting.

One of the major efforts was re-creating the sky. Around 15 feet of sky were missing from the painting. Gettysburg Foundation’s research team utilized Dr. Jacob’s weather reports to help the conservators envision what the sky looked like during Pickett’s Charge, the battle scene depicted in the painting. Thanks to Dr. Jacobs’ report, they knew that it was mostly sunny with thunderclouds during this infamous fight and was muggy with no breeze due to a looming storm.

This was one of only two primary sources used to re-create one of the most historic skies in American history. And, it all started with answering the age-old question, “What’s the weather?”

Sue Boardman is a licensed battlefield guide, Cyclorama historian, author, and the leadership program director for Gettysburg Foundation. Elle Lamboy is the director of membership and philanthropic communications for Gettysburg Foundation. Visit www.gettysburgfoundation.org.