The Forgotten Story of the Marines Who Died at Gettysburg

By James Rada, Jr.

Early in the morning of June 19, 1922, more than 5,000 Marines at the Marine Camp Quantico—more than a quarter of the Corps—marched onto waiting barges supplied by the U.S. Navy. At 4 a.m., four Navy tug boats towed eight barges up the Potomac River toward Washington, D.C. Meanwhile, tanks and artillery pieces towed by trucks rolled out along the Richmond Road headed for the same destination.

The (Baltimore) Sun noted that these Marines were ready for anything and had pretty much cleaned out Quantico of everything that could be moved. “The 5,000 men are carrying the equipment of a complete division of nearly 20,000,” the newspaper wrote. “In the machine-gun outfits especially the personnel is skeletonized, while the material is complete. Companies of 88 men are carrying ammunition, range finders, and other technical gear for companies of about 140.”

This army’s destination: Gettysburg.

Saving the Corps

At the end of WWI, politicians and some military leaders began talking about disbanding the U.S. Marine Corps. Maj. Gen. John A. Lejeune understood that his Corps needed to fight for survival in the political arena just as hard as they fought on the battlefield. He devised a campaign to raise public awareness about the Marines.

Instead of going to obscure places to conduct war games and train, he went to iconic places and put the Marines out in front of the public. At the time, the national military parks, such as Gettysburg, were still under the control of the U.S. War Department, which meant the Marines could use the parks as a training ground. Lejeune chose to do just that with a series of annual training exercises, which commenced in 1921 with a re-enactment of the Battle of the Wilderness.

The weeklong march took the Marines through Washington, D.C., and Central Maryland. Along the way, the Marines drew crowds that watched them march by. They also invited visitors into their camps to hear the band play or simply to talk with the Marines. Occasionally, they played baseball against local teams, and they always sought out any living Civil War veterans to invite them to Gettysburg to watch the re-enactments as a guest of the Marines.

They were an impressive sight, and they garnered a lot of public support and positive publicity during the march.

At Gettysburg

Camp Harding was set up on the Codori Farm and just north of the North Carolina Monument near the McMillan farmhouse. Various newspapers reported the ultimate size of the encampment to have been 65 to 100 acres.

Due to the planned stay of President Harding and his wife, Florence, in the camp for a night, the Marines constructed an 18-room tent, dubbed the Canvas White House, for the president and his guest. The tent included six bathrooms with tubs and running water, sitting rooms, bedrooms, and electricity.

- Reenactment of Pickett’s Charge at the battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania. William Sproul, Warren Harding and Elbert Lee Trinkle in front of tent.

- Marines during reenactment of Pickett’s Charge at the battle of Gettysburg.

- Reenactment of Pickett’s Charge at the battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. and John Archer Lejeune, center.

- Reenactment of Pickett’s Charge at the battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania. Smedley Butler, President Warren Harding, John J. Pershing, and John Archer Lejeune in front of canvas “White House”.

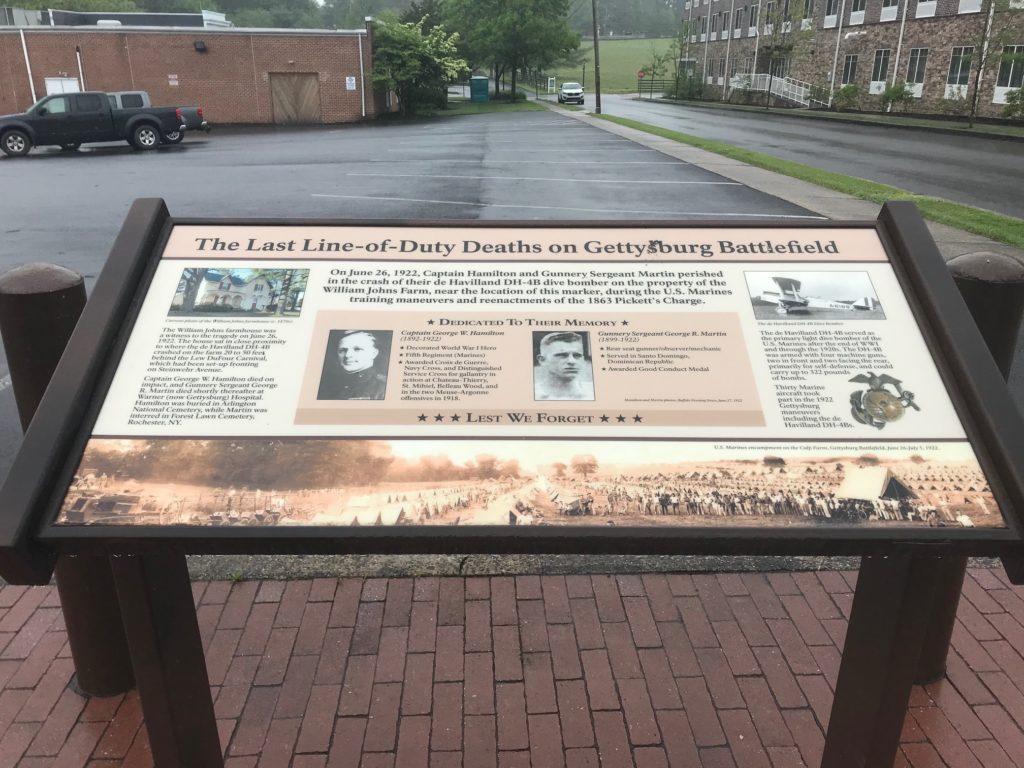

The Crash

Capt. George Hamilton, in command of a squadron of fighters providing “scout duty” while escorting the Marine infantry, along with Gunnery Sgt. George Martin, were flying a DH-4B fighter from Thurmont, Md., to Gettysburg on June 26. Hamilton’s De Havilland was at the rear of the formation of four planes. Nothing amiss among the planes was noticed until they approached the landing site at Camp Harding. Two of the planes landed safely in a designated portion of the fields near the intersection of Long Lane and Emmitsburg Road.

Hamilton and Martin’s plane went into a nose dive from about 3,000 feet up. It then became a tail spin. The plane crashed on the William Johns farm around 1:05 p.m., near what is presently the intersection of Johns Avenue and Culp Street in the Colt Park development. The Star and Sentinel stated the impact occurred within 50 feet of tents and equestrian equipment belonging to the Lew Dufour Carnival, which had set up along Steinwehr Avenue.

Marine officers stated that they believed Hamilton tried his best to avoid the crowds at the carnival, knowing his plane was in trouble and that the aircraft could have struck the carnival itself if he had continued to try and maneuver the plane out of its plunge toward the earth, possibly killing many people in the resulting crash.

Hamilton died at the scene and Martin died a short time later at Warner Hospital.

The accident is believed to have been caused by the difference in the reading of the altimeter at Quantico and Gettysburg. Quantico is on sea level, while Gettysburg is 600 feet above sea level. Consequently, when the altimeter reads 1,000 feet at the latter place, the actual distance is only 400 feet.

Hamilton and Martin were regarded as having been killed in the line of duty in the service of their country, and the deaths of the two Marines are presently the last military line-of-duty deaths on the Gettysburg battlefield since 1863.

A Memorial to the Fallen

Ronald Frenette read about this event in The Last to Fall: The 1922 March, Battles, & Deaths of U.S. Marines at Gettysburg by Richard D. L. Fulton and James Rada Jr. It moved him to take action. “I decided that it was important to bring forth information about these two brave pilots that have been overlooked by history. The best way to do that was to create a memorial,” Frenette says. He was subsequently joined in his effort by other residents, including Mike Tallent and Fulton.

On June 26, 2018, marking the 96th anniversary of the incident, the new memorial honoring Hamilton and Martin, was formally dedicated. The marker was installed at the intersection of Culp Street and Johns Avenue behind the Gettysburg Heritage Center, near the original crash site.

“We thought it was a great idea to tell a broader story, one that expands beyond the Civil War,” says Gettysburg Heritage Center President Tammy Myers.

The Re-enactment

The historical re-enactment on the anniversary of the Civil War battle attracted more than 100,000 spectators. Among them were president and First Lady Harding; Gen. John “Blackjack” Pershing; Pennsylvania Gov. Sproul; Virginia Gov. Trinkle; Acting Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.; U.S. Sen. George Wharton Pepper (Pa.); Commandant of the Marine Corps Maj. Gen. John A. Lejeune; Maj. Gen. Wendell C. Neville; Brig. Gen. Butler; U.S. Sen. Joseph Medill McCormick (Ill.); and Speaker of the House Frederick H. Gillett. Many foreign governments sent representatives to watch the re-enactments as well.

The New York Tribune described the battle: “Then they began to move forward…and for the watchers there was a thrill as though the ghosts of Pickett’s men were massed once more for another try for victory…there were six lines of men stretching along a mile front.”

Some of the advancing troops had also been provided with shotguns loaded with black powder rounds they would fire toward the ground, as the troops progressed to simulate artillery shell explosions. The Marines in the vicinity of the “explosions” would then fall “dead” or “wounded” around the detonation produced.

On July 4, the Marines brought out their airplanes, howitzers, hydrogen-filled observation balloons, tanks, machine guns, anti-aircraft guns, “Big Ear” monitoring devices, radio communications, and mortars to refight the battle as a modern conflict. It is the only time in history that the Confederate Air Force engaged in a dogfight with the Union Air Force.

Machine guns fired live ammunition, filling the air with tracers, and tanks rolled forward helping the infantry advance their lines. In the end, the Confederate Army won the second Battle of Gettysburg.