Gettysburg’s Artists-in-Residence program gives artists the chance of a lifetime.

Mark Mahosky knew it was an opportunity that he had to pursue. For more than 30 years, he had traveled to Gettysburg to create battlefield art. He knew the historic landmark well; traversed its famous knolls and valleys. He obsessed over its history.

As a child, he dreamed of what it would be like to experience the park as an artist. “Growing up in Williamsport, [Pa.,] it was just far enough away that I had to dream about Gettysburg, rather than being there all the time,” Mahosky says. “I kind of lived the Battle of Gettysburg through images and through books than walking the battlefield growing up. Subsequently, now I’ve done a lot more work on the battlefield and looked at it and inspected it a lot more closely.”

But never like he did during the month of August. He was one of three artists to spend a month living at Gettysburg National Military Park’s Klingel House through the Artists-in-Residence Program. The National Parks Arts Foundation created the residency program at parks throughout the U.S, including at the battlefield with support from Gettysburg Foundation.

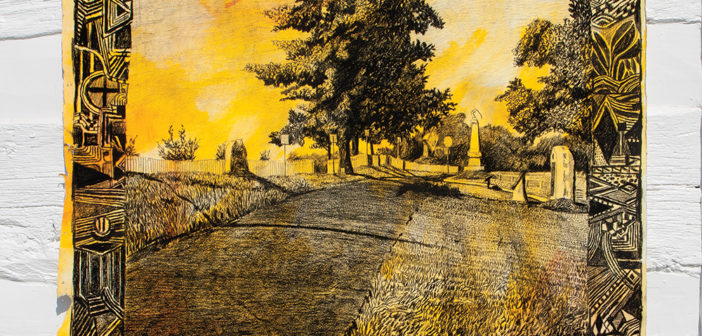

Mark Mahosky painting in the Peach Orchard.

“To prepare for the centennial at the National Park Service in 2016, the agency created a series of initiatives called ‘A Call to Action,’” says Gettysburg National Military Park Management Assistant Katie Lawhon. “We hope that the works of these artists will help engage new audiences. Art is such a fundamental way in which people connect with parks.”

While at the park, Mahosky and other artists are able to explore and create freely without expectations. Mahosky, a multimedia artist, did just that. He showcased his residency creations during a 45-minute presentation at the Klingel House in late August. The drawings illustrated the sanctity of the landscape at Gettysburg and the history of the park.

He and other artists spoke with park staff, explored the town, and cherished the opportunity to view the battlefield in ways that few have had the luxury to experience. And they found unique vantages of the park that inspired stunning new art.

During Ted Walsh’s tenure at the battlefield in September, he witnessed an event few see—a controlled burn of some of the grasses by the local fire department.

“One thing that I’m pretty excited to make a picture of is this burn they did,” says Walsh, a painter from New Jersey. “It is pretty cool. There are a lot of little stories that go with the monuments, or a certain general or certain group of soldiers. That will be interesting to work into some of my paintings. There are certain terms that I didn’t know. Witness trees, for instance.”

They soon could become art—and a part of the preservation of the park’s history, says National Parks Arts Foundation Founder Tanya Ortega.

“The need [for the residency]came from seeing [that]the parks themselves do not have a protocol for fine art,” Ortega says. “They have a protocol for archive of art that happened 100 years ago, but they don’t have a protocol for pursuing the future of fine art and contemporary arts in the national parks.”

Ortega is helping to bridge that gap through the residency program. “Just having an artist’s interpretation of the park has opened the hearts and minds of kids and adults,” Ortega says. “We don’t get to do that very much as adults. We don’t get to have our minds opened like when we were kids. Artists are able to touch that part of people’s minds. We’ve had people leaving the artists in residence’s studios in parks in tears because it is something they haven’t experienced in so long. The inspiration—we haven’t had this in the park in a public way since Ansel Adams, really.”

Like other artists who applied for the residency, Walsh was selected by specialized curators, a group of panelists, and even the park staff. The opportunity fit well with Walsh’s style and ideas.

“It fits in with what my art is and how people inhabit spaces over time and how we move through our own lives,” Walsh says. “Paintings, they stay still and it is forever and ever—unlike other things. I think that is a good metaphor for how the park is. Kind of frozen in time. They do all this maintenance to keep it exactly how it was. I’m going to try to mirror this in how it tries to stay still while moving through time.”

That’s the goal for both Walsh and the residency project.