Woodworker crafts historic trees into functional objects

By Alex J. Hayes | Photography by Casey Martin

Greg Allen’s retirement didn’t last long.

The founder and chief executive officer of the multi-faceted Gettysburg-based marketing company Graphcom stepped back from his responsibilities in January.

By March, he was turning historic trees into beautiful objects and a new career.

Allen is the owner and sole employee of Gettysburg Sentinels, fashioning products from trees that once grew where soldiers fought in the Battle of Gettysburg.

The wood is acquired legally from trees removed from the battlefield after they die, fall due to an act of nature, or are determined to not have been there in 1863. Wood is also harvested from limbs and branches removed to treat diseased trees.

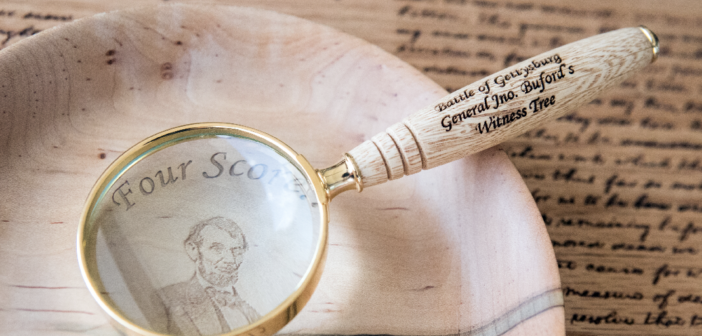

Allen works with Witness Trees, ones known to have been on the hallowed grounds of Gettysburg in July 1863, and Battlefield Trees, those that were on the battlefield grounds but not when Union and Confederate soldiers met here 159 years ago. He cuts the wood to size and uses a lathe to turn it into a variety of items including pens, bottlecaps, magnifying glasses, cigar cases, and letter openers.

“All of this Witness Tree wood is limited edition,” he says.

Allen’s friend, local historian Bill Hewitt, founded Gettysburg Sentinels in 2007 when he watched the National Park Service harvest trees and wondered what they did with the wood. With the park service’s focus on battlefield preservation, it often allowed tree removal companies to decide the wood’s fate. Many sold the wood to Hewitt, who began turning it into art.

Fifteen years later, Hewitt was ready to slow down at the same time his friend was ready for a new chapter. Allen, a lifetime history buff, had been a woodworker for more than 40 years but had never sold his pieces to the public. He bought a lathe and got to work, never realizing the products’ popularity.

“I am selling this stuff about as fast as I can make it,” Allen says.

Pens are the most in-demand item, followed by paperweights. The fondness for paperweights in today’s digital age surprises Allen, but he suspects their simplicity and price point are attractive to those who want to own a piece of the battlefield.

With his keen attention for detail, Allen ensures that a piece of wood that begins “not looking really pretty” is shaped into a smooth, sturdy, functional piece of art before it lands in a customer’s hands.

He places cut wood on a lathe turning at about 1,100 rotations per minute. Sometimes, he is in charge and moves the chisel as he pleases. Other times, the wood takes the lead and he must follow its grooves.

“The biggest challenge is getting the most out of the wood,” Allen says. “Sometimes a fat pen becomes a skinny pen because a piece pops off. I don’t want to waste it; it has a story to tell.”

The art of turning is much older than the historic wood Allen uses. Like most turners today, Allen uses an electric-powered lathe, but turners in the 1600s used foot-powered lathes controlled by a large wheel and twine. Human-powered lathes faded away during the Industrial Revolution to make way for water- and gas-

powered machines.

Once complete, Allen puts the piece into a laser engraver—a machine not even the most astute turner in the 1600s could have imagined. Each piece includes the words “Battle of Gettysburg” and the name of the tree from which the wood was derived. The machine does the work, but Allen’s keen eye ensures the lettering is clear.

The laser engraver gives Allen the opportunity to create many different-sized pieces, including a 10 ½-inch-by-10 ½-inch engraved copy of President Abraham Lincoln’s famed Gettysburg Address. Allen uses what is known as the “Bliss” copy of the speech, which is Lincoln’s final autographed manuscript and considered to be the most authoritative text. The size of the cursive handwriting nearly matches that of Lincoln’s, giving the plaque a historically accurate look.

The pieces’ historical qualities are equally as important as their artistic ones.

Witness Tree wood comes from nine sources, named from where the trees stood on the hallowed Gettysburg ground—Gettysburg Address Honey Locust, Abraham Lincoln Sycamore, General John Buford Oak, General James Longstreet Oak, Spangler’s Spring Walnut, Bloody Wheatfield Oak, Colonel Charles Costner Oak, Chaplain Horatio Howell Linden, and Camp Letterman Oak. Battlefield Tree wood comes from four trees in Pickett’s Charge, cedar from the Codori Thicket, and an oak from the High Watermark.

Information about where the wood came from and what happened in that area during the battle accompanies each creation. Holding a pen made using wood from the Codori Thicket, Allen reflects on the 200-some lives lost on that property.

“There were 5 or 10 minutes in the second day where a very outnumbered group of Minnesota Infantry was ordered by Hancock to fill this gap that he saw in front of the Codori Farm. He had no choice but to throw those guys into the fray,” Allen explains.

Today, the semi-retired Allen has a shed full of wood and more time on his hands than he did when was leading Graphcom.

He is excited to share his art—and the stories behind each piece.

Learn More

Find out more about Gettysburg Sentinels and the products made by Witness Trees

and Battlefield Trees at www.gettysburgsentinels.com.