New book sheds light on veterans’ addiction after

the Civil War

By Lisa Gregory | HIstorical images courtesy of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine

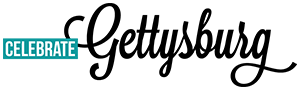

Unlike so many of his fellow soldiers, Alpheus Chappell survived Pickett’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. But he paid a great price, nonetheless.

“Chappell was a Confederate captain, and he led one of the charges at Pickett’s Charge. Halfway across the field, he was suddenly shot in the leg,” says Jonathan S. Jones, author of the upcoming book Opium Slavery: The Civil War, Veterans and America’s First Opioid Crisis and an assistant professor in the Department of History at the Virginia Military Institute.

Chappell was removed from the front lines and received medical care. “He was dosed with opium and morphine to deal with the pain,” says Jones.

As a result, Chappell became dependent on the medicine given to him. “I found a letter where he is describing how he can’t quit taking morphine,” says Jones. “Fast forward 20 years after the Battle of Gettysburg to the 1880s and, in so many ways, it has ruined his life.”

Chappell was not alone. Opioid addiction was a serious issue for many veterans following the Civil War. “Thousands of ex-soldiers died from overdoses,” says Jones.

We have been here before. As the United States battles an opioid epidemic that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates has taken 932,000 lives since 1999, another opioid epidemic began in the 1860s. And the stories are eerily similar.

“When I go back and read through some of these cases, they could come right out of the news in 2022— even though they happened 150 years ago,” says Jones, whose research for the book involved combing through records from the predecessor of the modern Veterans Administration system as well as newspaper articles and personal letters.

For instance, there’s the story of a young man barely past his teenage years found dead in a hotel room from an overdose. The man, Frank Clewell, died in 1867 and was a Civil War veteran.

“He had seen some hard fighting,” says Jones.

Clewell was captured and spent time in a prisoner of war camp, where he may have been exposed to disease, and treated with opium. “Then he goes back home, and the world of the South has been turned upside down,” says Jones.

One—or both—of those incidents no doubt played into Clewell’s addiction and ultimate demise, he says.

Jones describes opiates as “free flowing” during the Civil War. “You’ve got a lot of injured, sick guys,” he says. “It’s everywhere.”

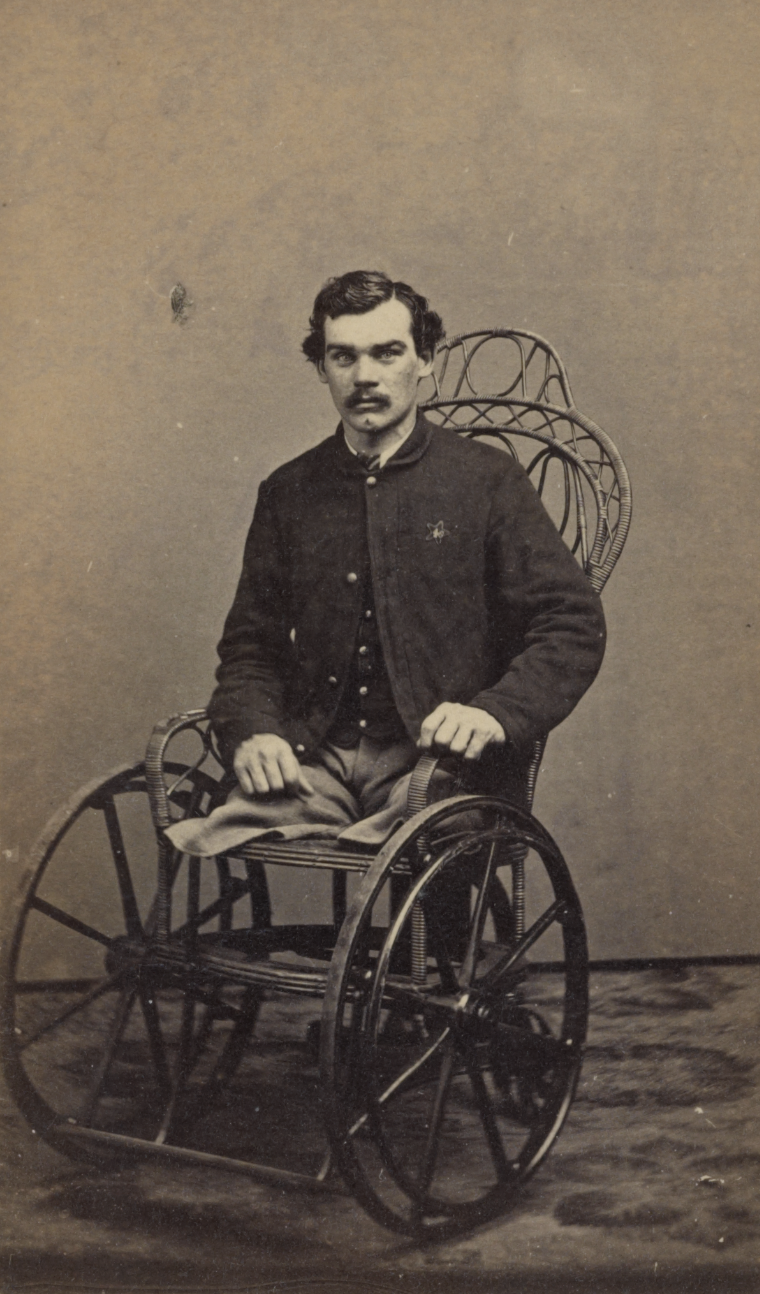

Medical care during America’s bloodiest war was gory. About three-fourths of operations performed were amputations. Gunshot wounds came from “bullets that would explode in your body and turn into a thousand fragments,” says Jones.

As a result, many of the injured would experience chronic pain and difficulties for the rest of their lives. Soldiers also were victims of diseases, such as dysentery, which ran rampant in camps.

For these injuries and ailments, soldiers were given opioid pills and morphine shots to relieve their pain and discomfort. In fact, it is during the Civil War, says Jones, that the hypodermic needle comes into popular use in the United States.

And, unlike today’s opioid epidemic, those tending to injured and sick soldiers with opioids were “just trying to keep soldiers in the field,” says Jones.

Yes, doctors knew that soldiers could become addicted, he says. “But they were just trying to help them survive the war.”

Sometimes the soldiers took matters into their own hands.

“There was a guy from an Alabama regiment who, every time he would go into battle, would take a dose of morphine because he thought that it calmed him down enough to actually go out and be an effective soldier,” says Jones. Understandably so, he adds, as “the ordeal that those Civil War soldiers were going through was just slaughter.”

However, injured or disease-stricken soldiers were not always treated the same. “There was this belief by white doctors, both from the North and South, that white people had more sensitive nerves and could feel pain more acutely than Black bodies,” says Jones. “Even when the soldiers are writhing in pain and screaming, and the doctors could see it with their own eyes. Just shocking.”

Pain medicine often was not given to Black soldiers as frequently; as a result, the 19th-century opioid epidemic did not seem to impact Black veterans as severely as it did their white counterparts, according to Jones. “I’ve actually found very few,” he says.

For addicted Civil War veterans, opioids were readily available. “Because opioids are so tightly regulated today, you don’t just walk into a pharmacy and buy a bottle of Oxycontin,” says Jones. “But back then there were no rules or laws or pharmaceutical regulations on these substances.

“They were for sale over the counter. You could buy them by mail. You could buy as much as you wanted and whenever you wanted, as long as you could afford it.”

This accessibility of opioids and the need for them would lead to the financial demise of those like Chappell, that Confederate captain injured at Pickett’s Charge. “Before the war, he had been a farmer, and he had a big family, wife, multiple kids,” says Jones.

Besides his injury hindering his ability to work his farm, Chappell was also spending money to support his habit. “He had to buy enough morphine to survive, which could really add up over the years and weigh on a family’s budget,” says Jones.

Chappell, in fact, became destitute, “to the point that he had to seek out a kind of 19th-century version of welfare from the state,” says Jones.

The veterans also had to grapple with the stigma of being an “opium eater,” as it was referred to at the time. Many veterans and their families struggled in silent shame as addiction was often seen as more of “a moral problem than a medical problem,” he says.

In his book, Jones describes a woman seeking her widow’s pension after her husband, a Civil War veteran, died of an overdose. “He had gotten addicted to laudanum, which is a kind of opioid,” says Jones. “One day he accidentally took too much.”

Getting a widow’s pension tended to be easy, explains Jones, as long as women could prove they were married to a Civil War veteran who had died—but not in the cases of deaths caused by opioid overdoses. However, he says Congress awarded a special pension to the widow in this instance.

But President Glover Cleveland would have none of it. “Cleveland goes behind Congress’s back to victim blame the deceased soldier for basically being unmanly and for not just sticking it out and gritting his teeth through his pain,” says Jones. “And this isn’t just one case but was really a widespread phenomenon.

“Just like it is now with a lot of families when their son or father or brother would die of an overdose, they didn’t want to admit it to anybody,” Jones continues. “It had been a secret for decades, and they wanted to keep it a secret all the way to the grave.”

This stigma was even more devastating when one was considered a war hero.

“Pickett’s Charge is celebrated after the Civil War by southerners as being the moment when the South could have won the war,” says Jones. “So, people who were in Pickett’s Charge were at the forefront of Southern culture in the decades after the war. The people that almost saved the South. And Chappell is not just a participant in Pickett’s Charge, but one of the leaders, and he becomes addicted to morphine. In culture and memory, they were one thing, but, in reality, addiction made them something else. It’s an incredible tragedy.”

There were glimmers of hope, though. Some in the medical profession at the time, although they were few, viewed addiction differently. “They had this idea that it was a disease of the brain and not the soul,” says Jones.

Unfortunately, this change in thinking would come too late to help Civil War veterans struggling with addiction. The Civil War opioid epidemic ended as the years passed and Civil War veterans like Chappell slowly died out.

But lessons linger from that first opioid crisis to the current one. And, Jones says, we should take note.

“If these Civil War veterans, who are held up on a pedestal and lionized, can suffer from this stigmatized problem, so can any of us,” he says. “And I hope that that reduces some of the stigma around opioid addiction today.”

Stepping Up to the Battle Again

Gettysburg’s Mercy House is the First Substance Abuse Recovery Center in Adams County

History has come full circle in the most hopeful of ways.

Mercy House, the first substance abuse recovery center in Adams County, is a link between the opioid epidemic that afflicted Civil War veterans and the current one that’s now ravaging lives.

Prior to its current use, Mercy House had served as a convent for the Sisters of Charity, who helped care for wounded soldiers during the Battle of Gettysburg. Many of those same injured soldiers would go on to struggle with their own addiction in the nation’s first opioid epidemic.

Now Mercy House is stepping up to the battle again. “There was a time when you either knew someone who had overdosed or you didn’t,” says Marty Qually, an Adams County commissioner. “Now more know someone than don’t.”

That includes Qually himself, who lost a college friend to an overdose. An average of 14 Pennsylvanians die every day from an overdose, according to the Pennsylvania Office of the Attorney General.

Mercy House provides a public space for clients and residents to receive information, counseling, and other addiction services. The facility, part of the state’s Recovery Advocacy Service Empowerment (RASE) program, can also house up to seven men in recovery.

With so many lives touched by the opioid epidemic, the community has been eager to show support for Mercy House, which is funded in part by Adams County. According to Qually, support for the facility has come from a range of sources, from a local church to a local reading group to name a few. “We need to fight this,” Qually says. “The cost is getting too high.”

Mercy House

45 West High St., Gettysburg

717-420-5219